Keble and The Great War

Chaplains in the War

A unique aspect of the contributions made by Keble men who served on the front lines in World War I is the significant number who served as Chaplains to the Forces. Of the 966 Keble Members who served in uniform, at least 202 were Chaplains (1921 Role of Service).

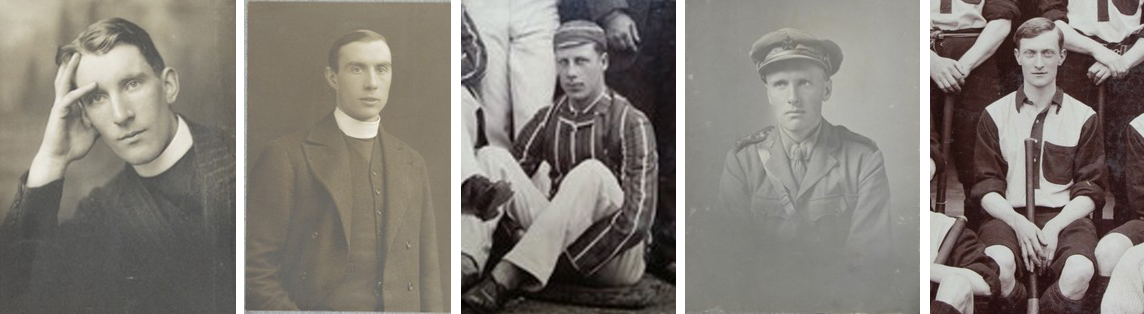

Chaplains in the War: The Revd Oswin Creighton (1901), The Revd Edward Reginald Gibbs (1904), The Revd Robert Mansel Kirwan (1880), The Revd Benjamin Corrie Ruck-Keene (1908), The Revd Robert Morley Henderson (1899).

An oft controversial and criticized vocation in books of history, the role of Chaplain in the War has been reclaimed in more recent historical writings which recount the job of the Chaplain ‘to minister to his men at all times and especially in times of danger and distress, before going into action and when wounded or dying. He must be at liberty to go where this duty leads him, even to the front line’ (William Temple Papers, Thorold to Temple, 25 November 1938).

In the First World War, the number of Chaplains in the Royal Forces increased from fewer than 200 in 1914 to more than 3,500 in 1919. Of those who served, records show that 179 of these Chaplains were killed in active duty before the Armistice (Michael Snape and Edward Madigan, eds. Clergy in Khaki, 2013; 3). 11 of those killed in action were Keble men, who comprise a shocking proportion of Chaplains who died. These Chaplains included The Revd William Herbert Freestone, a member of Keble’s 1st VIII in 1903-1904, who was killed in action on 14 December 1916; The Revd Arthur Henry Marsh, a member of the 1st Lawn Tennis Team, who died in action from the effects of poison gas on 7 October 1918; and The Revd Edward Reginald Gibbs, a member of the 1st Rugby Football XV from 1906-1908, who was killed by a shell as he returned from conducting a soldier’s funeral on 29 March 1918 (The Yorkshire Evening News, Friday 15 April, 1918). Keble Chaplains served with a myriad of regiments, from the Grenadier Guards to the H.M.S. Chester, and from their diaries we know they spent time in the trenches during the battles of Somme, Jutland, and Ypres (Chaplains always served unarmed).

The Role of the Chaplain, through the eyes of The Revd Alfred Llewellyn Jones (Keble 1901)

15 September [1916], Friday: …The day was a full one – and many sad sights and narrow escapes took place…stretcher bearing – giving drinks to Germans and our own – marking wounded for bearers to find – with rifle upside down – bayonet stuck into the ground. A word here and there encouraging and helping to organize. It was more interesting and thrilling – terrifying if one had time to think about it…(Excerpt from the Diary of The Revd Alfred Llewellyn Jones [Keble 1901], Keble College Archives)

The Revd Alfred Llewellyn Jones, who served on the front lines in France and whose unpublished diary may be found in the Keble archives, describes the role of the Chaplain well in the opening quote. Chaplains, better known as padres, were called ‘not to oil the wheels of war but to help the humanity caught up in it’ (The Revd Clinton Langston, BBC, ‘Army Chaplains’). Llewellyn Jones recalls the Major General reminding the Chaplains in 1918 ‘about our duty in dispelling grumbling and fostering ésprit de coups. He also asked us to preach action rather than belief and to emphasise the character of Christ as courage rather than humility’ (23 January 1918). Nevertheless, Chaplains were not only present on the front lines for spiritual support and sermons, but also spent much time assisting wounded soldiers with practical needs such as letter writing. Llewellyn Jones recounts in his daily diary that many mornings are spent writing letters for soldiers who have difficulty reading or writing or who are wounded as well as letters of sympathy to families. As a more recent history of Chaplains is clear, ‘in their correspondence with the families of fallen soldiers, moreover, chaplains also provided an important channel of communication between the army and a civilian population that suffered unprecedented levels of bereavement’ (Clergy in Khaki, 3).

Chaplains also conducted services for the troops, both on Sundays and before most battles, often using whatever space they could find in the trenches or the woods and whatever vessels they could acquire from ruined churches nearby. Llewellyn Jones writes without a hint of embarrassment that he and another Chaplain ‘visited the Cathedral where we looted a standard lamp for carrying in Procession. Nearly caught by a shell while there’ (28 April 1916). He also offers a rather poetic view of a service on the front lines in France:

The out of doors [service] with the altar cloth flapping in the wind and the aeroplanes overhead and an occasional shell bursting fairly near and our guns making a crashing noise and the young life with the trees and flowers around us all made a wonderful effect.

(9 April 1916)

Apart from moral and spiritual support, letter writing, and services of worship, one of the main roles of a Chaplain to the Forces was to conduct funerals and burials, something they did on a daily basis at times. Llewellyn Jones recounts many funerals throughout his diary, as well as the location of graves and cemeteries on the battlefield. Many of his days are described in similar ways to these select excerpts:

Writing letters after breakfast. 5.9 direct hit on our dugout. Tree brought down and 6 men killed in the Platoon. Many wounded. The whole day very heavy fire. We sat in false security all morning and enabled many to shelter in our home, Generals Fielding and Hayworth amongst them. Took funeral at Essex Rd Cemetery at 9.30pm…11.15 burial 6 of Kings Company in one grave. A hard day, and sad.

(20 March 1916)

I went up to dinner with 4th GGs in the trenches. I buried an Irish Guardsman whose body I found lying out. Also buried a couple at 4thGG HQ. Back late, about 4am.

(11 September 1916)

Buried 7 men in one shell hole and dug a grave for a Scots Guardsman and buried him. Had experience again of being shrapnelled while digging and being uncomfortably near 5.9s. Saw some splendid work by gunners driving ammunition lorries up through shell fire.

(12 September 1916)

When visiting the trenches, Chaplains could see the brutality of the battlefield and as recounted in the lives of Chaplains Stephen Clarke and David Railton (Keble Old Member), many wanted to administer last rites to those in No Man’s Land. Llewellyn Jones tells of his attempt to do this being prevented by the Commanding Officer when he writes that, ‘I asked CO and Brigadier whom I met in the line if I might bury some of the men in no man’s land – they wished me not to go – so I returned’ (11 August 1916).

Nevertheless, this did not keep Chaplains off the battlefield, which they visited often to serve as stretcher-bearers and to tend the wounded and the dead. Furthermore, their work and proximity to the Front Lines meant that shells and gunfire were a continual threat. In two detailed entries, Llewellyn Jones describes the battlefield and its surroundings.

Up at 2.50am. Met Col. H. Seymour at Brigade HQ and went round trenches with him…Back to dugout by 7am…Service for Kings Co 10.0 and No4 10.45. Walked round to see some of the gunners…Then up to Menin Gate. Shelling hard had to shelter and get on from cover to cover. Went through the Sally Port to Menin Cemetery 9.45pm…Two funerals. Back to Brigade HQ. Very heavy shelling. Many horses killed and men wounded. Graham 1st GGs wounded and a man near to me – whom I carried under cover with another man to help…I really did think that I was going to get hit and felt wonderfully thankful to get through untouched.

(6 May 1916)

Later in the day I visited much of the battlefield. It was Hell. Bodies, flies, smells, shells, helmets, picks, shovels – all kinds of horrors and the desolation of it. Parry and I got 17 men cleared from one shell hold…2 had been killed since they had been put there and all were much exhausted from lying out since yesterday about 5pm. One was a German…We were shelled pretty well too. We tried to cut across to 4th Battn it was awful…again in the evening took up a work party and some stretcher bearers – very heavy shelling…Returned from 4th GGs about 4am.

(10 September 1916).

Near the cemetery the [Germans] hated us a good deal – one shell about 50 yards away caused panic to our team of horses…another shell came within 10 yards – a dud – or perhaps this would not have been written…there was a good deal of stuff flying round which made the journey not too pleasant but nothing hit me.

(16 December 2016).

The Tomb of the Unknown: The Revd David Railton (Keble 1904), Chaplain

While Keble has a history of strong ties with Westminster Abbey, including Keble Warden Eric Abbott who left Keble to become Dean of Westminster, many might not be aware of the connection between Keble and the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in the Abbey.

The Revd David Railton was a Keble Old Member and Chaplain to the Forces, who served with numerous regiments (the 18th Battalion Northumberland Fusilliers, the 103rd Infantry Brigade, the 1/19thBattalion London Regiment, and the 19th Division in France) and was awarded the Military Cross in 1916. He was described as ‘a good padre who was often seen in the trenches’ (Neil Hanson, The Unknown Soldier) and as his grandson recalls, ‘Like many padres on the front, it was clear to him that…distress was suffered by those who could not be told where their husband, father or son was resting, but who had at best a general map reference as to where he may have fallen’ (Camden New Journal, 1 July 2011). For Railton, the idea of the Grave of an Unknown Warrior changed that and as a Chaplain to the Forces, he is the one who first proposed the idea for the honoured grave.

As recounted in the writings of Llewellyn Jones above, Railton also encountered an unspoken number of men who were killed in action and who had no known grave. This experience led him to appeal to Field General Douglas Haig with the idea that an unknown soldier should receive a national burial service in Westminster Abbey. He received no reply to this appeal but did not let the idea go and following the War, wrote to the Dean of Westminster who did reply and who brought the idea before the Prime Minister (Hanson, The Unknown Soldier). Railton himself writes years later,

The idea came to me, I know not how, in the early part of 1916 after returning from the line after dusk to a billet at Erkingham near Armentieres. At the back of the billet was a small garden and in that garden, only about six paces from the house, there was a grave. At the head of the grave stood a white cross of wood on which was written in deep black pencilled letters, An Unknown British Soldier of the Black Watch. How I longed to see his folk! But who was he and who were they?… How that grave caused me to think!

(www.stjohnschurchmargate.org.uk).

Thus, because of the persistence of a Keble Chaplain to the Forces, the Grave of the Unknown Warrior continues to provide a lasting reminder of the sacrifice made by so many.

Written by The Revd Dr Jenn Strawbridge, Chaplain 2010-2015