History Features

Copyright History and The Light of the World by William Holman Hunt

Legal historian Dr Elena Cooper (CREATe, University of Glasgow), the author of ‘Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image’ (CUP, 2018) and curator of the online exhibition ‘Copyright and Painting in the Nineteenth Century’ (RHUL, 2025), casts new light on this famous painting, viewing it from the perspective of copyright history.

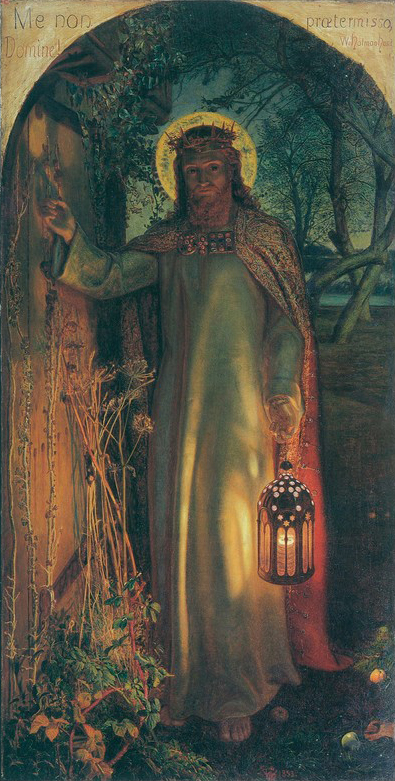

William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World is well known today as an iconic image of the nineteenth century: in the Victorian era, the image circulated widely and was engaged with by all classes of society, not just through reproductive prints but also through the tour of a later version of the painting across the British Empire. At Keble College, Oxford, you can see the original painting — Hunt’s first version — which the College acquired in 1872 some twenty years after it was first painted in 1851-52. While the history of the painting has long been known, from the meticulous work of art historians Judith Bronkhurst and Jeremy Maas, less well-known is the story of the painting told from the perspective of copyright history.

Dr Elena Cooper giving a talk in the Keble side chapel entitled “Art and Copyright in the Nineteenth Century: A talk before Hunt’s The Light of the World”. Photograph by Susanna Brunetti.

Dr Elena Cooper giving a talk in the Keble side chapel entitled “Art and Copyright in the Nineteenth Century: A talk before Hunt’s The Light of the World”. Photograph by Susanna Brunetti.

To view The Light from the perspective of copyright history, means to travel back in time to a point where, in the words of one judge, a ‘beautiful array’ of copies ‘meets the eye at every turn’ Chief Justice Erle in Gambart v Ball (1863); reproductions of visual art were displayed for sale widely, both in the windows of printsellers’ shops and by street-hawkers. These copies included authorised engravings of popular paintings, for which painters were paid high prices: Hunt’s The Light was engraved by William Henry Simmons and published by printseller Gambart in 1860, for which Hunt was paid £200 (the equivalent of £19,000 today).

Also in circulation, were unauthorised photographic copies, of smaller size than the engravings and far cheaper in price. In Gambart v Ball, which concerned The Light as well as Rosa Bonheur’s The Horse Fair, the courts held the smaller unauthorised photographs to infringe Gambart’s copyright in the engravings. The argument that the smaller and cheaper photographs were not ‘copies’ as they ‘address themselves to a totally different and distinct class of purchasers’ — those who could not afford the authorised engravings — was irrelevant; a smaller photograph infringed the engravings as it ‘conveys the pleasure to the mind’ of the original.

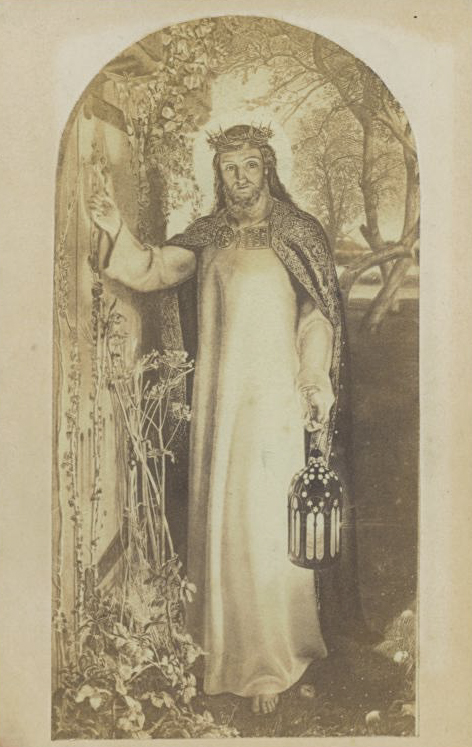

Unauthorised photograph of Simmons’ engraving of The Light of the World by Hunt, carte-de-visite, 1860s.

Yet, despite this favourable ruling, Gambart and other printsellers wanted quicker and cheaper means of pursuing photographic infringers. In 1862, new copyright legislation was passed: the Fine Arts Copyright Act. As well as introducing copyright in photographs and paintings, it enabled claimants — such as printsellers — to recover penalties for copyright infringement in magistrates courts, which was far quicker and cheaper than proceeding in the higher courts. However, there was a technical difficulty (relating to how the various Acts were drafted) which prevented cases concerning copyright in engravings being heard by magistrates.

In view of this difficulty, what could the printsellers do? One solution was for printsellers to rely on copyright in the painting, i.e. they would argue that an unauthorised photographic copy of an engraving, was also an indirect copy of the painting (as the engraving was a copy of the painting). Yet, in the case of The Light, there never was any copyright in the original painting as it was first sold before painting copyright had been introduced in July 1862. Accordingly, Gambart registered copyright in an authorised photograph of Simmons’ engraving; before magistrates, where a printseller also owned engraving copyright, relying on an authorised photograph of an engraving was long accepted — until its challenge in Graves Case (1869) — as a means of recovering penalties for infringement of engraving copyright (even though there was no copying from the photograph in which copyright was claimed).

Handling the unauthorised photograph of Simmons’ engraving of The Light of the World by Hunt, demonstrating its size.

As well as featuring in a highly complex story of how nineteenth century copyright regulated reproduction in different media, The Light was also well known by the Victorian public because of the further two versions of the same painting, also in oils: a smaller version now held by Manchester Art Gallery produced roughly contemporaneous with the Keble original, and a later far larger version, which today hangs in St Paul’s Cathedral. Here, the story of The Light is interesting for what it reveals about how artists justified the right to repeat paintings they had sold, in the same media as the original, i.e. a second version of an oil painting, also produced in oils.

In the late nineteenth century, collectors sought to reform copyright law so they could stop painters subsequently repeating paintings they had sold without a collector’s consent: a painting’s financial value was determined by its uniqueness, so the existence of a repetition would diminish the value of the original. Painters including Hunt, were outspoken in resisting these pro-collector proposals: for painters, the repetition of a painting was akin to a performance or re-telling of a story, and they sought to justify that right in a number of ways. In an article published in The Nineteenth Century, in 1879, Hunt argued that ‘due protection of the artist’s claims’ was for the ‘good of the community itself’, and this public interest argument perhaps explains his decision to paint a further version of The Light. Hunt had been unhappy that Keble were not caring for the original adequately — the painting was hung in the library over hot water pipes — and when the College placed it in a new side-chapel, it began charging an admission fee for the public to see the painting. The further version painted by Hunt, therefore, was to ensure its public access, and it was that version — not the Keble original — that went on to tour the Empire, and in 1908, it was presented to St Paul’s Cathedral. Interestingly, as was not uncommon at this time, copyright was registered in this later version, despite parliamentary debates in 1862, which indicate that later versions should not qualify for copyright protection, on the basis that they were not original works.

The later St Paul’s version differs in some respects to the Keble original, and, interestingly, copyright records have proven valuable to art historians today, in dating one of the features of the St Paul’s version: the halo in the finished St Paul’s version is thinner and more distinct than the Keble original. The halo in the photograph of the St Paul’s version of The Light (held at The National Archives, in relation to copyright registration) does not bear these features and supports the view that the halo was changed — to be thinner and more pronounced — after 20th January 1904 (the date of the copyright registration). By this time, the painting was in the hands of Hunt’s studio assistant Edward Robert Hughes (due to Hunt’s failing eyesight) so this change was most likely the contribution of Hughes, not Hunt.

Photograph of the later version of The Light of the World by Hunt, currently held by St Paul’s, accompanying the copyright registration application dated 20 January 1904 (The National Archives, London, COPY1/211)

In the nineteenth century, the use of studio assistants was not without controversy, as art was valued by the hand that painted the work, and this too influenced the shape of artistic copyright; co-authorship (which might have founded claims to authorship by studio assistants) was intentionally not mentioned in the 1862 Act and the art fraud provisions safeguarding accurate attribution of paintings, were also intended to penalise painters who applied their signature to works that were in fact painted by their studio assistants. While no such claims were made against Hunt, the existence of these legal provisions indicates the complex interests at stake in negotiating art in the nineteenth century.

References:

J. Bronkhurst, William Holman Hunt: A Catalogue Raisonée, Vol. 1 (Yale University Press, 2006

E. Cooper Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (CUP, 2018)

E.Cooper ‘The ‘Visual Turn’ in Copyright History and its Relevance to Art History’, The Burlington Magazine, 2021, Vol. 163, No. 1425, p.p. 1148-1157.

E. Cooper, Painting and Copyright in the Nineteenth Century, (RHUL, 2025), online exhibition available here: https://tinyurl.com/p6z7bkec

Gambart v Ball (1863) 14 CB NS 306; 143 ER 463

W. Holman Hunt, ‘Artistic Copyright’ (1879) The Nineteenth Century, 418

J. Maas, Holman Hunt and the Light of the World (Aldershot, 1984)