History Features

The Founding of

Keble College

AD 62/3/3 – Caricature of an encounter between a Keble student and a student of another college

Changing Times

Keble College was born against a background of change and in the face of further change at Oxford University.

The Oxford University Act of 1854 radically altered the structure of governance, both at University level and at the Collegiate level. As well as establishing the Hebdomadal Council (a governing body of the University), it introduced the “Executive Commissioners” who over the next few years “set about remodelling Oxford”. The commission forced the colleges to change their statutes, and the structure of their governing bodies. Such changes reduced the powers of heads of house and eroded the dominance of clericalism. This led to fears by many that Oxford, traditionally the seat of education for Anglican ministers, was eschewing Church principles, and was becoming governed by dangerous academics.

In tandem with this, there was a growing realisation of the need to increase the number of spaces at the University, and make a University education attainable for more people – known as “University extension”. As early as 1846 a committee of the Hebdomadal Board urged that a university education should be made available to those currently unable to afford it, and that this should be done by the foundation of a new college. In 1865 several sub-committees drew up plans for University extension. One of these sub-committees considered a plan for a college for those who needed a more affordable university education, which would also increase the supply of clergymen to the Church of England. A member of this committee was a close friend of John Keble’s and a fellow Tractarian, Dr. Pusey. Pusey showed the plans of the committee to Keble shortly before his death. Keble highly approved of them.

Fundraising

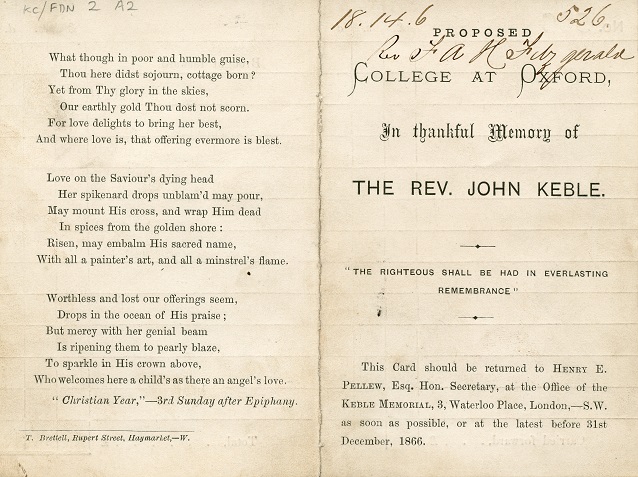

On the day of John Keble’s funeral, 6 April 1866, a group of his friends and supporters, including Dr. Pusey and H.P. Liddon (fellow Tractarian and acolyte of Pusey), met to discuss establishing a fitting memorial to Keble. They decided the best option, and the one most in keeping with Keble’s wishes, would be to found a college at Oxford in his memory, and bearing his name, which would provide an inexpensive university education on Church of England principles. The method of funding the proposed college was unusual. Traditionally, colleges at Oxford had been founded through a very generous donation from a single benefactor. Previous attempts to establish a new college had failed, and it was assumed that the days of “ancient munificence” were over. However, Keble’s supporters decided to use his widespread fame and popularity as a means of fundraising. They would raise money through public subscription and “afford to those many persons who love and revere the memory of the Author of The Christian Year some opportunity of publicly expressing their deep gratitude”.

KC/FDN 2 A3 – Collecting card no. 1255 of Rev. T H Waters

The Keble Memorial Fund officially had its first meeting at Lambeth Palace on 12 May 1866, and immediately began advertising the scheme in national newspapers. Furthermore, they sent out circular letters to individuals – including as an enclosure to the 1866 University Report on the Foundation of a New College or Hall at Oxford. The Fund estimated they would need a total of £50,000. By the end of 1867 they were able to purchase the Parks Road site from St John’s College, and on 13 March 1868 they had raised over £25,000 with an additional £10,000 pledged.

The piecemeal nature of the fundraising did lead to some challenges. The College had to be built in sections in order to meet budgetary constraints, with living and teaching space given a priority. On 6 May 1870, the fund treasurer felt compelled to write to the Fund’s standing sub-committee, reporting that the memorial fund was nearly exhausted, and that unless additional money could be raised, the College would open with a £5000-£6000 debt. In response, the Fund committee practised strict economy, cutting the planned number of staff and deferring activities such as the turfing of the quad. The magnificent chapel, library and hall were only afforded by generous donations from the Gibbs family. It is perhaps because of the lack of an initial large benefaction that Keble College became one of the first colleges to forge excellent alumni relationships, raising funds from its previous attendees.

“Not a poor man’s hall but one which is adapted to the… tastes of gentlemen who wish to live economically”

It was one of the key principles of the Memorial Fund that the College should cater to those who could not afford to attend the traditional colleges. A large part of the expense of such colleges was due not to the educational aspect of students’ time there, but rather to the lifestyle choices and traditions in place. Students were expected to furnish their own rooms (buying furniture at inflated prices from local suppliers); they paid their scouts directly, commissioned personal meals and ate in their own “sets” of rooms, and were expected to throw lavish parties to entertain guests.

KC/FDN 1 A4 – Minute book of the Keble Memorial Fund Sub-Committees 1866-1870

To counter this, Keble was the first college to offer a collegiate education at an “all-in” charge. In a meeting on 12 February 1870, the Fund’s standing sub-committee decided that they needed to charge each student £80 a year, without entrance fee. This would cover rooms, furniture, facilities – everything except laundry and lights. Food was supplied, but no meals were to be taken privately – everyone would eat together in hall. As a further cost-saving measure it was agreed to provide a room for undergraduates to use as a reading room (saving personal expenditure on books) but this was to be supported at their own expense. In this, Keble proved to be a template for other colleges and their attempts to reduce costs.

However, economy was not simply to be a College measure; it must also be embedded in the ethos of its students. Every term, a report was supplied to the College’s Council of those who had prudently spent less than £3 on their battels (money that students had to pay back to the College) and those students were commended. Those who had spent more than £5 were condemned as “exceeders”. Persistent offenders were encouraged to move to institutions more suited to their tastes.

A Charter Like No Other

The changes implemented by the commissioners following the 1854 University Act had significantly decreased the influence of clericalism amongst the colleges’ governing bodies, and nibbled away at the powers of the heads of house. Further changes planned by the Government (which came to fruition in the 1871 abolition of religious tests) led to concerns as to how best to preserve the Church of England ethos on which the College had been founded. The answer came in the shape of a very unusual Charter. As noted by the Privy Council, in a letter to the Memorial Fund on 26 May 1870 the Charter “differs very materially in form from all the Charters, especially the later ones by which Colleges at Oxford and Cambridge have been incorporated by the Crown”. The charter makes no mention of Fellows. Instead, an unprecedented amount of authority was granted to the Warden, and an external council would be responsible for the financial solvency and efficiency of the institution. Furthermore, there was no requirement for the College to be in Oxford.

The first page of KC/GOV 1 A1/4 – Keble’s Charter of Incorporation

Whilst the Charter was granted by the Queen on 6 June 1870, the path to acceptance by the University was a rocky one. As early as May 1870, Pusey reported objections on the Hebdomadal Council, primarily over whether the College should have the status of a private hall (which would give the University far more control over the institution) and the College reserving the right to move away from Oxford. As the debate carried on, Convocation had to pass a special decree in order for students to matriculate before the nature of the relationship between the College and University was firmly settled (which led to further protests). Eventually, following further debate and vocal opposition from such activists as Thorold Rogers (a former Tractarian) and H.A. Pottinger (known as a strong anti-clerical and agnostic) the College was incorporated into the University by means of a new statute of Convocation – “On New Foundations for Academical Study and Education” – on 18th April 1871. The statute, subject to certain conditions (such as having suitable buildings, and a royal charter) gave the institution the same privileges as other colleges and halls, with minor reservations, such as the heads of such houses not being given the same privileges as heads of older houses. However, it “practically admitted all members of Keble to the same position and rights as members of all other Colleges”.

Going Forwards

Keble disappointed those who thought it would become a theological college, producing religious extremists. As early as 1876, during the open of Keble’s new chapel, Archbishop Tait confessed he had had fears of Keble being a “monkish institution” but it had proved nothing of the sort. Warden Talbot emphasised that the College did not simply produce candidates for holy orders, but its graduates went on into all walks of life.

KC/JCR 1 C1/3/2 – Black and white photograph of a dinner in Hall to celebrate the College gaining full status

Over the years, Keble has changed – in 1930 the College tutors became fellows, and the whole internal administration of the College was made over to the Warden and Fellows. In 1952, new statutes were drawn up by Vere Davidge, removing “all anomalies” from Keble’s governance. On 9 April of that year, in a statute approved by the Queen in Council, Keble was made and declared to be for all purposes a College of the University.

Although circumstances have changed, Pusey’s words on the day of the College’s foundation still ring true:

“It was not a mere plan to bring up those who could not afford the expenses of ordinary Colleges. It was to extend the College system, but it was more. It was to found a College which would react upon the rest of the University: which should have a character of its own, of which all our members should, whatever their several capacities, be real students; … which should not be divided into good and bad sets… but whose esprit de corps it should be to knit in one by the mutual intercourse and friendship of all with all”

Written by Faye McLeod, Archivist & Records Manager, as part of a display celebrating Keble’s 150th anniversary.

Back to features