History Features

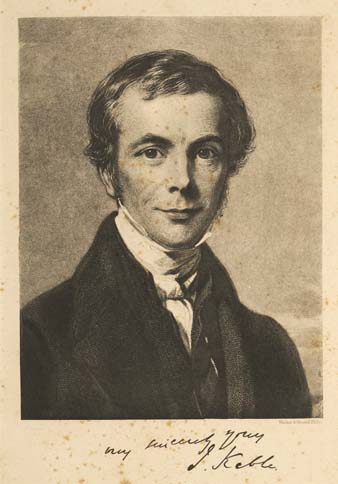

John Keble

An autographed copy of an engraving of a young John Keble by George Richmond

John Keble and The Oxford Movement

John Keble’s assize sermon “National Apostasy”, preached in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford on 14 July 1833, is widely regarded as the beginning of the Oxford Movement. In the words of John Henry Newman (theologian and poet) “I have ever considered and kept the day, as the start of the religious movement of 1833”. The sermon was effectively a call to arms for the Church of England.

The UK had recently seen radical political and social change in a short period of time. Due to the established nature of the Church of England (essentially centuries of entwining between Church and State) Keble and his followers saw such changes as an attack upon the Church. For example after 1829, Roman Catholics were allowed to sit in parliament, which meant that non-members of the Church of England could have a say in how the Church was run. Keble’s sermon explored this relationship, and argued that such disrespect for the Church was inexcusable (and a sign of individual moral deficiency). However, he also used the opportunity to expound his theories on the “true” source of the Church’s authority – that of apostolic succession. Keble argued that the line of bishops, consecrated by the laying on of hands, could be traced back to Christ himself, and that the Church of England was the representative in England of Christ’s global and eternal church.

Such a belief was closely related to Keble’s belief in the “authenticity” of the primitive church and his reclamation of practices such as private confession and daily services. These ideas held wide appeal in Oxford in the early 1800s, and through his role as a college tutor and respected academic, Keble’s ideas spread. Something of a retiring figure, especially following his departure from Oxford in 1823, Keble nevertheless became the unofficial figurehead of the Oxford Movement, providing a discreet but firm steering hand to other figures – for example, acting as editor to the tracts that disseminated the religious ideals he had inspired (and provided the name “Tractarians” to the Movement).

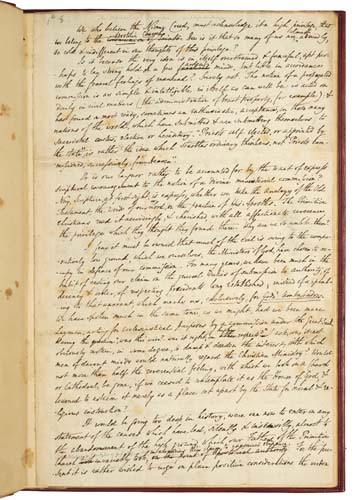

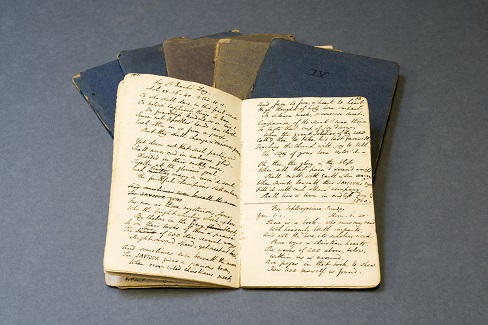

AD 1/KM 12 – Keble’s Manuscript Copy of Tract IV

Although preferring to remain in the background, Keble would, when he felt it necessary, publicly defend the Tractarian cause. In the flashpoints over theology and the relationship between Church and State generated by cause célèbre prosecutions he wrote treatises, petitioned bishops and archbishops, and published protests. In the case involving his own curate, Peter Young, Keble had to be dissuaded from deliberately provoking his own prosecution in a court of law.

Keble’s Personal Life

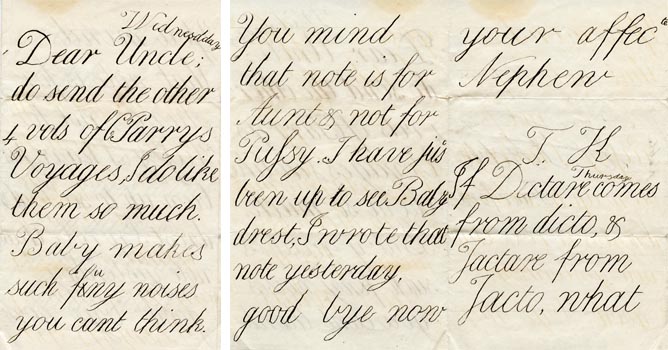

Born in 1792, the second of five children to the Reverend John Keble (Vicar of Coln St Aldwyn) and Sarah Maule, John Keble grew up in the family house in Fairford, Gloucestershire. The kindness and compassion for which he was known throughout his life are evident in the large amount of correspondence directed to him from strangers seeking religious or moral guidance, but are never so clear as in his interactions with his family and close friends. The letters are filled with nicknames, such as ‘Pekin’ and ‘Pussy’, and even those discussing matters of national importance frequently turn to the concerns of domesticity.

AD 1/CP/KF/21/1 – Letter from John Keble’s nephew to John Keble

Following his marriage to Charlotte Clarke in 1835, Keble took up the parish of Hursley, where he remained as vicar until his death in 1866. Keble revelled in his role as a parish priest, introducing daily services, teaching at the village school, providing allotments and wholesome entertainments, and embedding religion into daily life. It was from this “cultivated obscurity” that Keble was, nevertheless, to make his mark upon the world.

Keble’s Academic Achievements

Although typically self-deprecating, Keble was recognised as something of an intellectual prodigy. In 1807, aged 14, he won a scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He gained a double first (only the second person in the history of the University to achieve this feat) in mathematics and classics at age 18. It would seem that Keble’s path was set to be one of academic stardom – becoming a bachelor fellow at Corpus shortly after his graduation, being elected to an Oriel fellowship in 1811, and becoming a College tutor in 1818. Keble, as was required for almost all fellows in this period, took holy orders in 1815. Despite his academic success, Keble was, at heart, a clergyman. Whilst dazzling amongst Oxford’s intellectual glitterati, his letters to close friends speak of his disillusionment: “What a delightful thing it is for tutors and carthorses to have a resting day in every week” (Letter to Mrs Pruen, 1821). In 1823, Keble resigned his positions in Oxford, in order to serve his parish full-time. Yet, he was never to be entirely free of the pull of Oxford, being elected Oxford Professor of Poetry in 1832, following the success of his debut volume of poetry, The Christian Year.

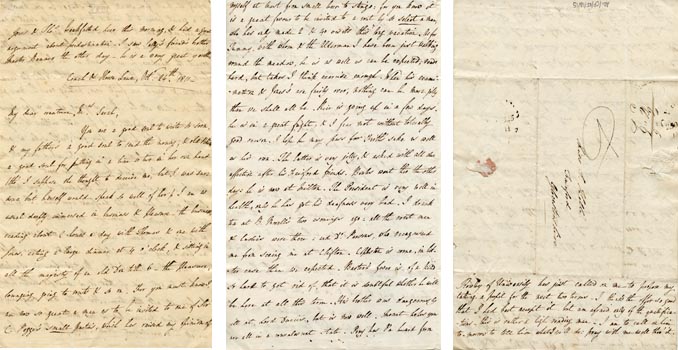

AD 1/CP/KF/13/15 – Letter from John Keble to S. Keble on life as a new Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford

Keble’s Writings

It was following Keble’s decision to attend full-time to the needs of his parish that his poetic output increased. Inspired by his countryside rides and walks, many of the poems look at nature through meditative eyes, as an avenue towards deeper understanding of religious mysteries. Although initially shy of publicity, Keble was at length persuaded to publish his poems in 1827, as The Christian Year. The volume assigns a poem for each Sunday and some feasts of the liturgical year. The volume was initially published anonymously, but following the book’s success, Keble eventually acknowledged authorship. The book was wildly and enduringly popular, combining a reverence for God and nature whilst being firmly emotionally reserved. Over 95 editions were published during Keble’s lifetime, along with many copies of his later poetry compilations such as Lyra Innocentium and a metrical translation of the Psalms.

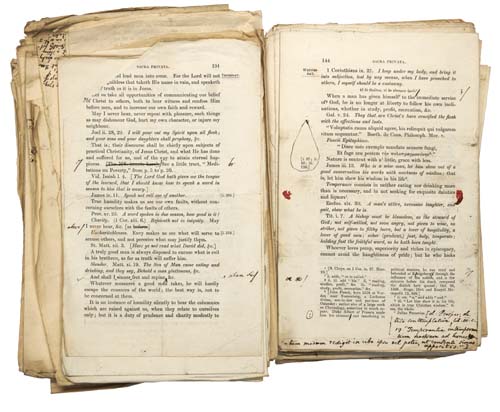

AD 1/KM H&P 10 – The Manuscripts of the Christian Year

Keble is also notable for his biographical and editorial work on earlier English theologians – choosing those who, perhaps unsurprisingly, fed into his religious philosophy. His Works of Richard Hooker (published 1836) provides a scholarly edition of the major works of a man who is now widely recognised as the father of the Anglican “middle-path” between Protestantism and Catholicism. One of his last works published before his death, The Life of Thomas Wilson, Bishop of Sodor and Man (published 1847-1863) was the culmination of 16 years’ work on the life of a man notable for objecting to State interference in Church matters.

AD 1/194c – Keble’s Page Proofs for the Life and Works of Bishop Wilson

Legacy

John Keble passed away quietly on 29 March 1866 in Bournemouth. He had only consented to be absent from his beloved parish as he thought sea air would be good for the health of his ailing wife. The village of Hursley was a sea of black on the day of his funeral, attended by many notable personages of the day. Venerated not only for his poetry, his intellect, and his religious beliefs, Keble was loved for his holiness, his kindness, and his charity.

An example of a Victorian memento mori – a lock of Keble’s hair, kept as a keepsake, following his death

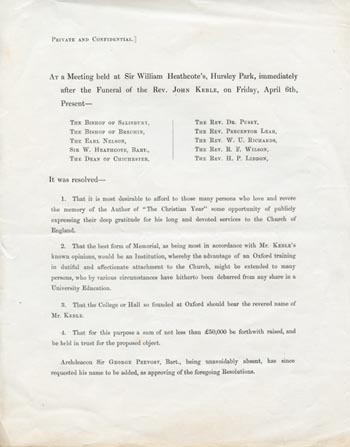

It is little wonder that on the day of his funeral, his friends gathered to discuss what would be a fitting memorial to the man who through his beliefs and words had changed the course of the UK’s religious history.

KC/FDN 1 A1 – Printed copy of the resolutions of a meeting held at Hursley Park after the funeral of John Keble

Written by Faye McLeod, Archivist & Records Manager, as part of a display celebrating Keble’s 150th anniversary.

Back to features