History Features

Construction and Opening of the College

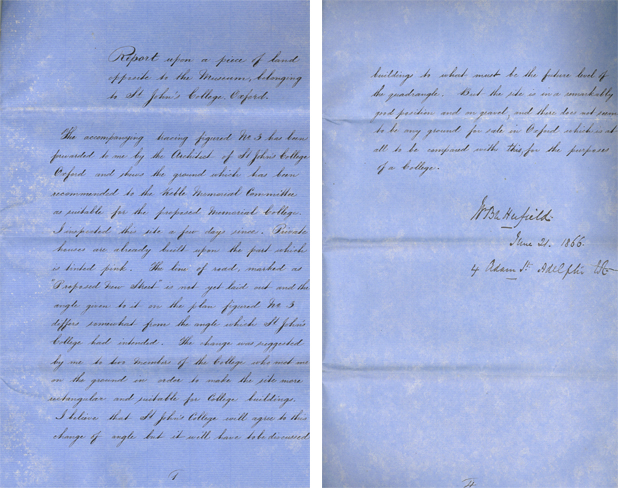

KC/FDN 1 E/1 – Mr Butterfield’s Report upon the Proposed ‘St John’s College’ Site, 21st June 1866

“There does not seem to be any ground for sale in Oxford which is at all to be compared with this, for the purposes of the College”

The final line of the architect, William Butterfield’s, report on the suggested site for the new college is a ringing endorsement. Owned by St John’s College, opposite to the University Museum, the site offered space close to the centre of the city, in an area of rapid development. The report shows the necessary genesis of one of the College’s most notable features – Liddon quad’s sunken lawn. Although used as ground for allotments by the time of the report, the site had originally been a quarry and Butterfield noted that a good deal of foundation work would be necessary to bring up the buildings to what he saw as the future level of the quad. In fact, the College ended up having to buy earth to bring the pathways up to the level of the buildings. The four-acre site was eventually purchased on 29th January 1868, for a cost of £7,047. Butterfield’s immense vision quickly became apparent.

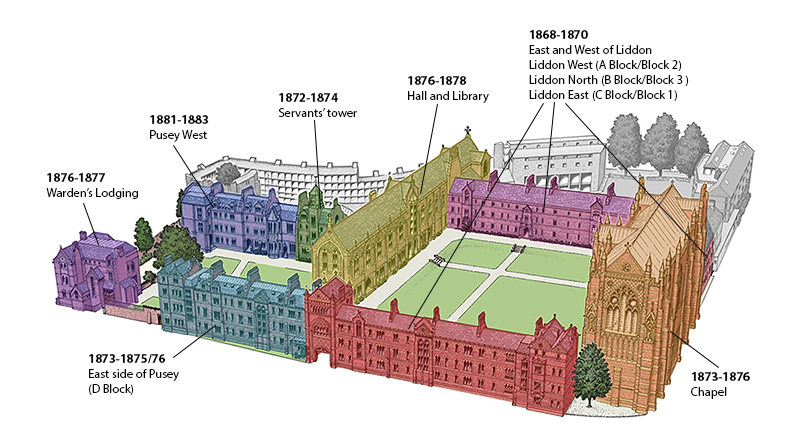

Colour-coded image of the College buildings

“It would be a disgrace to us if our labours ended in a mean and contracted College… We ought to have imposing buildings occupied by a large number”

Much as the method of fundraising for the College was incremental, so was the process of construction. Butterfield’s original plans for the College were for blocks A, B and C. They would provide accommodation for 101 undergraduates and 6 tutors, a kitchen and buttery, and a gateway. The accommodation was of an unusual design. Eschewing the traditional Oxford staircase arrangement, undergraduate rooms were arranged along long corridors, with tutors’ sets positioned at the ends.

Despite a relatively small-scale beginning, these buildings exhausted almost the entirety of the memorial fund. Nevertheless, one of the main agenda items for the first College Council meeting of 16 June 1870, was the need to raise additional funds for further building (known as the Keble College Extension Fund). Such work quickly became vital, as the number of students rapidly increased, more than doubling by October 1872. A servants’ block (with clock tower) was begun in 1872 to accommodate staff, and the plans for “D Block” (providing accommodation for 40 undergraduates and 3 tutors, and a porters’ lodge) were approved in June 1873.

AD 62/3/29 – Black and white photograph of the west and north ranges of Liddon Quadrangle, Keble College, before the Chapel was built

As the Council had resolved that all future buildings should be to accommodate additional undergraduates it was inevitable that the planned “public” buildings were not given priority. However, one generous family saw the need for such shared spaces. In October 1872, it was minuted that the businessman and philanthropist, William Gibbs, had agreed to pay the full amount for Butterfield’s proposed chapel – roughly £30,000. The chapel can be regarded as Butterfield’s pièce de résistance but it was not without its controversies – notably the Council’s refusal to have it consecrated (fearing religious interference) and Butterfield’s choice of altar mosaic. Sadly, William Gibbs did not live to see the opening of the Chapel, but his sons carried on his generosity. Antony and Martin Gibbs gave the funds that enabled the College to build the Hall and Library. Fittingly, the foundation stone for these was laid on the same day as the opening of the Chapel.

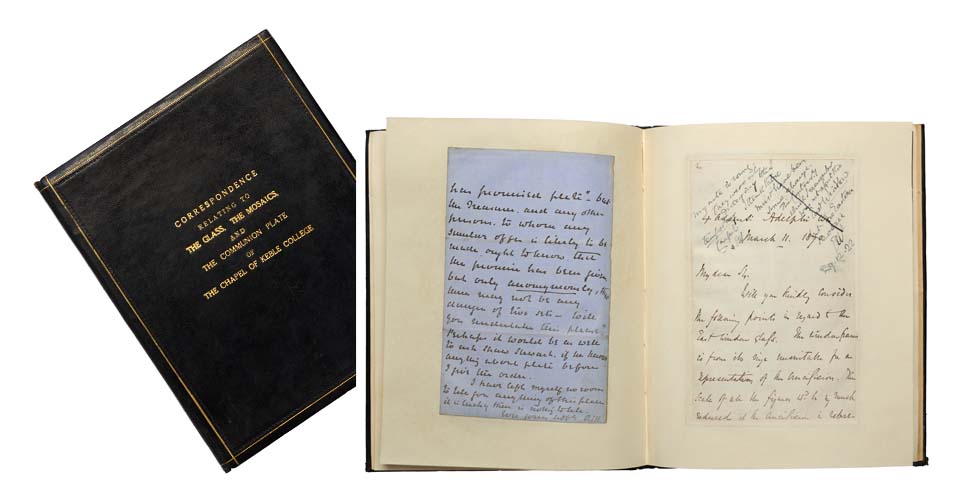

KC/CHA 1 A/5 – Correspondence concerning the disagreement regarding the mosaics in the chapel of Keble College, 1873

One building that the College struggled to raise funds for was the Warden’s Lodgings. Edward, Lavinia, and their growing family had been “temporarily” housed in joined sets of rooms in the corner of Liddon quad for almost seven years. As D Block neared completion, the College decided to take out loans to build the Warden’s lodgings, including a mortgage of £4,000 from Edward Talbot’s mother. Although modest by Oxford standards, The World complained that “the home of asceticism and prudential sanctity has built its Warden a ‘lordly pleasure house’”!

The final Butterfield buildings were constructed between 1881 and 1883, providing accommodation for staff and the still growing number of students.

AD 62/3/2 – Black and white photograph of Parks Road frontage of Keble College

The Red Letter Days

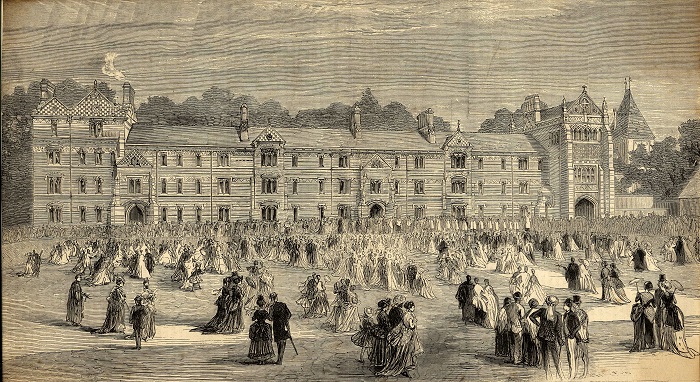

With each new section of building a display of generosity and support for the fledgling College, it is little wonder that each opening was the cause for large celebrations. Such events also cemented the College’s position within the University and advertised its success, with heads of other colleges and the press being invited to the festivities. These were always scheduled for St Mark’s Day (25th April) – John Keble’s birthday, and were approached by College authorities with the same administrative rigour that they applied to matters such as the granting of the royal charter.

The opening of the hall and library in 1878 had the following itinerary:

8am – Holy Communion

9.30am – Breakfast

11.30am – Procession, Matins, Procession, Dedication of the new buildings

1.30pm – Lunch

5pm – Procession, Evensong

7pm – Dinner (consisting of 22 dishes, including Claremont soup, oyster patties, and Duchess pudding)

KC/FDN 4 B2 – Mounted print of the opening of the College

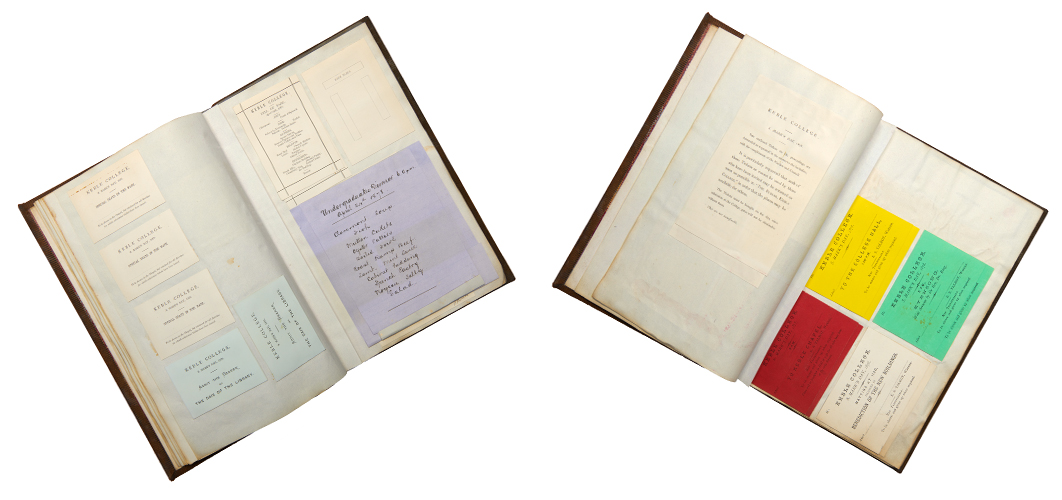

These were scrupulously organised, requiring printed invitations; colour-coded tickets; passes (waiters, servants, trade, reporters); an order of service booklet; seating cards; bill of fare; seating plans; booklet of working arrangements for chapel staff; a separate booklet of working arrangements for hall and lodge staff; and a 100 page log of invitations issued and replies received.

Pages from KC/FDN 4 E1 – Scrap book relating to St Mark’s Day ceremonies, 1878

All of this planning does seem to have been worth it – the event went so well that the Steward was awarded a ten guinea bonus and Lavinia Talbot simply stated in her diary “I shall say nothing but that St Mark’s day week was a huge success… the speeches were good and so was the food the Bursar gave”.

The Gibbs Family

William Gibbs (1790-1875) was a noted businessman and religious philanthropist, reputed to be “the wealthiest commoner in England”. His father’s bankruptcy in 1789 and resulting precarious finances left its mark on the young Gibbs, causing him to be withdrawn early from school, and never to attend university.

Portrait of Williams Gibbs

His business acumen was proved early on in life, when he restored the Cadiz branch of the family firm to profitability. His big break came in 1842 when his firm signed contracts with the government of Peru to be the sole importers of guano (a valuable fertiliser) to Britain. A fierce marketing campaign and the success of the product led to soaring prices, enabling Gibbs to retire in in 1858 and concentrate on his philanthropic works. Both he and his wife, Blanche, had visited Rome in 1838, confirming their affinity for the Oxford Movement. This devotion can be seen in the choices of recipients for his generosity – building churches for the clergy of the Oxford Movement, and acquiring advowsons – seeing this as a “practical attempt towards the regeneration of Christian England”.

His family continued his generosity following his death in 1875. Blanche funded scholarships, and built and endowed convalescent homes. Two of their sons, Antony and Martin, provided the funds enabling Keble College to build its hall and library.

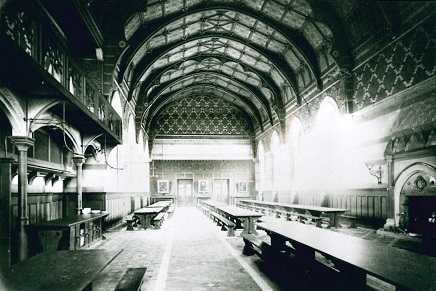

AD 115/7 – Black and white photograph of the interior of the Hall, Keble College

Written by Faye McLeod, Archivist & Records Manager, as part of a display celebrating Keble’s 150th anniversary.

Back to features